The New York City Subway: A ludicrous concoction of clashes

- Liz Publika

- Apr 15, 2019

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 19, 2025

The New York City subway is a triumph of contradictions. Enter the underground passageway and turn the corner to encounter a vibrant mosaic freshly speckled across an aging concrete wall. Beneath the masterpiece, find the collective detritus of a million commuters consisting of foil wrappers, old receipts, and some sticky substance that should definitely be avoided. Then board a steel train, a testament to modern engineering, to loudly hurtle through the congested guts of a modern metropolis, as the winding history and dizzying stimuli of its decaying transit system temporarily engulf you.

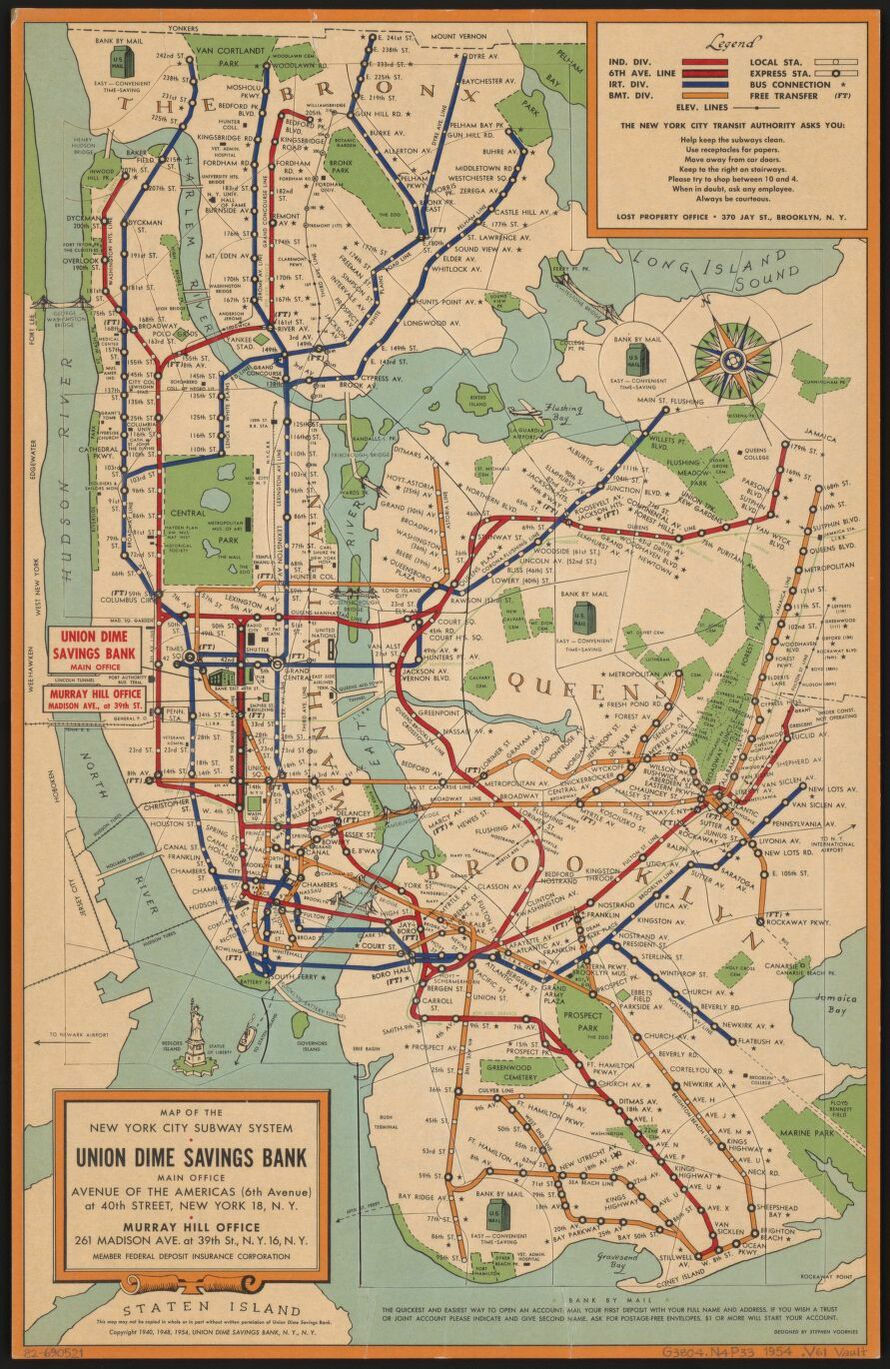

The NYC subway is the busiest mass transit system in the United States, but only the sixth busiest in the world. It was officially opened on October 27 of 1904 by Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT). Since then, it's gone through many changes. Some were subtle — tokens were phased out in favor of paper and plastic cards; a mishmash of fonts and signs were unified into a clean Helvetica typeface; maps and expanding train routes became color-coded. Others have been nothing short of seismic — the price hike from $0.05 to today's $2.75; the subway's massive growth; and its transition from a private to state-operated enterprise.

Before 1904, the city offered mass transit in the form of “els,” or elevated trains, but because of the densely packed and bulky infrastructure needed to support them — and the fact that steam-powered trains severely polluted the streets from high above — a more efficient approach to rapid transit was needed. Although the idea of moving underground was debated for over 20 years, blizzard-related concerns ultimately sealed the deal. The day it opened, the IRT "line ran approximately nine miles from City Hall North to Grand Central Station, then west to Times Square and up the West Side to 145th Street."

The New York Times reported:

“The official train made its run exactly on time, arriving at One Hundred and Forty-fifth Street in exactly twenty-six minutes, all along the way crowds of excited New Yorkers were collected around the little entrances talking about the unheard trains that they knew were dashing by below, and waiting eagerly for the first passengers to emerge from the underground passageways at their feet...Much as the Subway has been talked about, New York was not prepared for this scene and did not seem able to grow used to it.”

There was a learning curve. When the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit system (BMT), previously known as the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) before its bankruptcy in 1919 and restructuring in 1923, entered the emerging subway market, it made the unusual decision to run wooden cars that had originally been used on elevated lines in its new underground system. That practice ended in 1918 after one of those wooden cars derailed in a subway tunnel near Prospect Park, killing 93 passengers. In the decades that followed, both the subway system and its train cars underwent significant evolution.

In the early 1920s, the NYC mayor proposed a new plan — an elaborate series of city-owned and operated mass transit lines that would compete with the BMT and IRT. And so, the New York City Board of Transportation was formed; it oversaw the creation of the Independent Subway System (initially ISS, later IND), which opened its first line on September 2nd of 1932. By 1954, however, all three rapid transit systems were made into one city-operated enterprise known as the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA), which also operated the city's public buses.

As for the trains themselves, the IRT’s composite cars combined wood and copper exteriors with fabric and steel interiors, but they initially lacked enough doors. As a result, conductors were responsible for manually opening and closing station gates until the system was modified in 1910. Five years later, the company introduced its stainless steel Pullman trains, which featured fabric seats. That same year, the BMT unveiled the Standard, a subway car with steel bodies that were wider and longer than those used by the IRT. When the IND entered service, it introduced its R-type cars, which were larger, faster, and equipped with more doors. Modern subway cars are direct descendants of these R-model designs.

Although air cooling technology was something the subway systems were trying to figure out since the summer of 1905, according to the New York Transit Museum, these attempts were less than successful. It wasn't until 1967 that the engineers were able to implement efficient air-conditioning on the New York City subway, much to the collective relief of all New Yorkers. At this time, NYCTA became part of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which is responsible for public transportation within the state of New York today.

By the 1970s, however, innovation significantly slowed down and train maintenance worsened. By the start of the following decade, the now-notorious grittiness of the New York City subway became a daily part of life. As a response to the pollution and graffiti, the MTA introduced the “Great White Fleet” in 1981 — a total of 7,000 train cars painted in a pristine shade of white in an effort to deter the street artists — “which predictably had about the same effect as trying to curb drawing by handing out clean, white sheets of sketch paper.”

Since 1989, trains have not been allowed to leave their yards if graffiti is visible on their exterior, but passengers can still spot fragments of graffiti art within the stations. One of these is Brooklyn's famous Masstransiscope. Created by Bill Brand in 1980, the work is similar to a zoetrope since passengers see “an animated cartoon, not 228 hand-painted images” as they ride past it. Although no longer accessible, a notable mention is Williamsburg's 2009 Underbelly Project — on an " IND line that was never opened...over the course of a year, street artists PAC and Workhorse invited 100 street artists in and out of the station to create work there overnight."

The 21st century brought about new features and developments, like the Kawasaki produced R-160 models of 2002, which were based on the proven designs of the R-142A and R-143 subway cars. In 2018, the MTA announced plans to purchase a new generation of R-type cars featuring major upgrades, including redesigned exteriors with LED headlights and interiors equipped with Wi-Fi, USB ports, full-color digital displays, security cameras, door-opening alerts, and an open gangway design. These new R-211 cars were expected to enter service in 2023.

While NYC awaits its newest train car fleet, it's hard not to think back to IRT's now-abandoned City Hall Station, where the storied history of the city's subway system began nearly 115 years ago. Featuring 400 feet of curves, teeming with “stained glass, Roman brick, tiled vaults... brass chandeliers…[and] three panels of glass skylights,” its funny to acknowledge that the skylights are blackened with tar, and the space is shuttered for good. The New York City subway system is a master class in absurd contradictions — a ludicrous concoction of clashes that somehow makes the most sense in the world.

Note* Images sourced from the Library of Congress