The Science of Love, Art and Beauty: Interview with neuroaesthetics professor and artist Semir Zeki

- Liz Publika

- Aug 27, 2022

- 13 min read

Updated: Jan 3

by Liz Publika

You’re at a fancy dinner party. It is attended by people of different ages, ethnicities, and cultures, but everyone is dressed to the nines. There’s plenty of food and drinks flowing, as people are amicably chatting away and toasting to life. Suddenly, every attendee stops what they’re doing and silence envelops the room. You realize that the party is staring at the entrance, the last guest has arrived and she is nothing short of absolutely stunning.

“The quickest way at any dinner party to end a conversation dead in its tracks is to say that ‘beauty is subjective anyway,’” explains Semir Zeki, “but it’s not.” He would know. The distinguished neuroscientist and professor at University College London (UCL), studies the neural correlates of affective states, like love, desire and beauty. In fact, according to Zeki, when we say that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” the statement is both true and not.

Zeki’s original area of research was on the visual cortex; he showed how the brain processes attributes, such as color and movement, through specific brain areas. Using electrophysiology and brain imaging, he showed that there’s no “final common path” for visual experience.

The thing is, the brain processes different types of visual information separately both in time and space. Through psychophysical studies, for example, he discovered that we become aware of color a fraction of a second before form or movement. Turns out, activity in each visual area can induce a conscious correlate without necessarily reporting to another cortical area. Or, simply put, visual consciousness is not unified.

His interest in art and the visual experience led him to explore the brain mechanisms underlying human responses to beauty, a field for which he coined the term neuroaesthetics.

His more recent work, however, involves studying the brain reaction to affective states generated by sensory inputs, such as the experience of love and hate. His studies of the experience of visual and musical beauty has led him to suggest that a specific part of the brain, field A1 of the medial orbito-frontal cortex, is critical for such experiences, which brings us back to the dinner party; some aspects of beauty appear to be universal.

ARTpublika Magazine had the pleasure of speaking with Semir Zeki about his research pertaining to beauty, love, and how our brains process them.

What do neuroaesthetics allow you to learn about the human brain?

It is extraordinary that one can have an experience that is so abstract and so pervasive, but which always correlates with activity in a specific area of the brain. Moreover, the intensity of that activity can be measured in relation to the intensity of the declared experience of beauty. In other words, when I find something more beautiful, the activity in an area is more intense. And if we decided — I am not sure if I agree with it, but it’s certainly an important part of it — that science is measurement, [rather than method and measurement,] then we have pulled the study of beauty very much into the scientific fold.

Secondly, what surprised me enormously is the experience of mathematical beauty, which we classify as biological beauty and which correlates with activity in the same part of the brain. And it’s also parametrically related to the intensity of beauty felt by mathematicians at the sight of their beautiful equations. This brought many mathematicians out of the closet, they love beauty but they were ashamed to admit it. When people came out of the scanner and I asked them about how they felt emotionally, they were all so moved at the sight of some of the equations, you’d think they just saw Michelangelo’s sculpture.

When you’re talking about seeing something beautiful and the activity it ignites in the brain, does that mean you made a judgment about it?

There’s a part of the brain, which registers green but does not care about what object that green belongs to. It is only interested in the color green. Then there’s another part of the brain that is interested in the direction of motion, but does not care about what is moving in that direction. Now, in a way, we can also say that there’s a part in the brain that is interested in the experience of beauty — which correlates with the experience of beauty regardless of source.

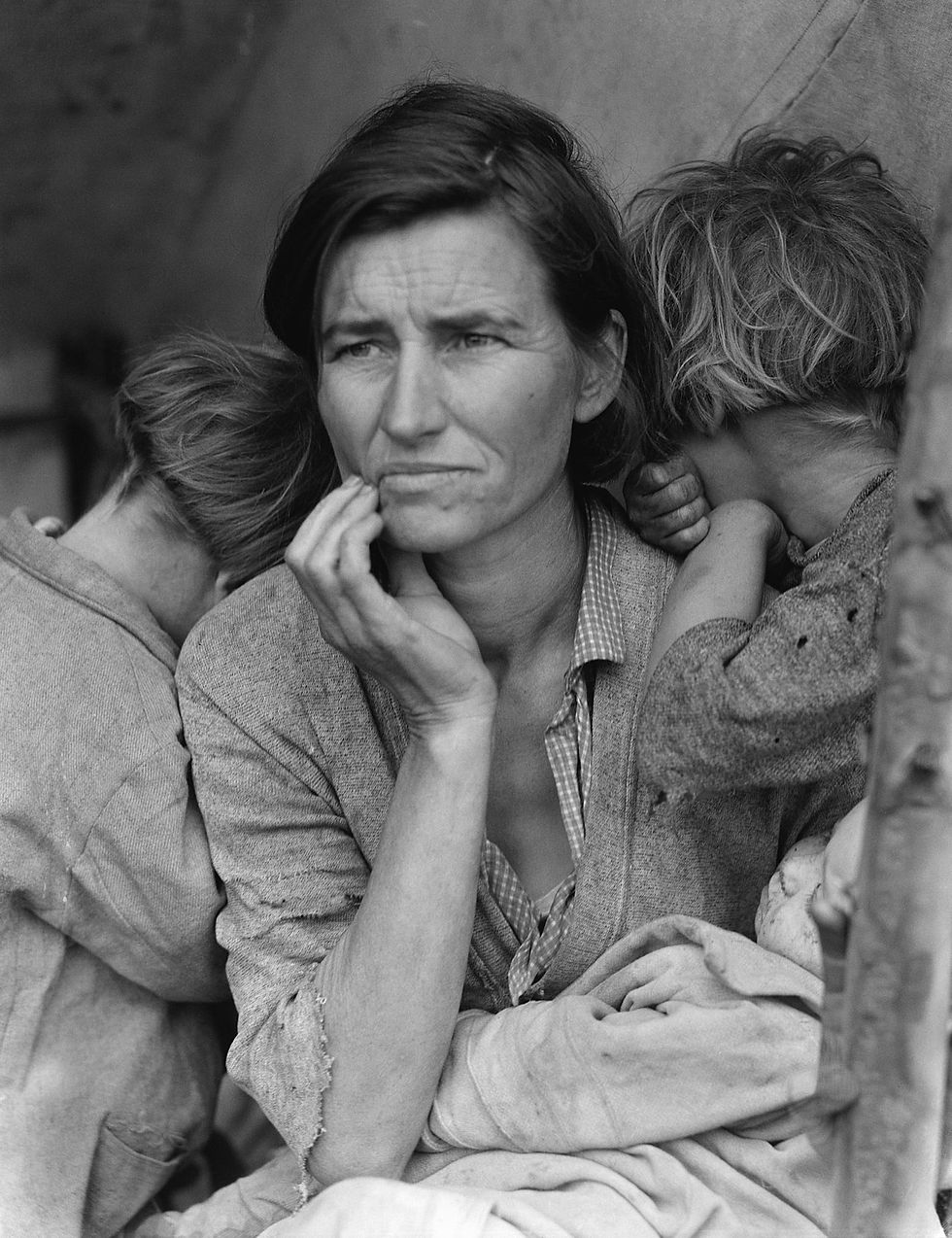

In the philosophical literature of aesthetics, people always speak of beauty in the abstract — beauty derived from music, poetry, and painting. Take, for example, beauty derived from sorrow. In our experiments, we used iconic photographs of the Great Depression by Dorothea Lange, which are very beautiful but sorrowful pictures.

Beauty from sorrow and beauty from joy are both experiences that correlate with activity in the same general region of the brain — the medial orbitofrontal cortex, or what I call field A1 because it is quite large. In that sense, there is an abstract quality to beauty in that it doesn’t have to be tied to any particular medium.

But, there is division when we experience biological beauty and artifactual beauty. Let’s take, for example, a very beautiful Japanese face, which people will find beautiful within the Japanese culture but also in Italy, or America, and so on. The conclusion that we can draw is the experience of beauty is not quite as subjective as people may think.

Now the experience of artifactual beauty, like buildings, may affect people differently. A person may be more affected by the design of a church if they are Christian, or by a Mosque if they are Muslim, or more by a Buddhist temple if they are Buddhist. And for somebody who had grown up in a country where people lived in Igloos, maybe igloos are very beautiful to them. In other words, you are not born with a concept of habitation but you are born with a concept of a face.

But to answer your question more completely, yes, one definitely makes a judgment and field A1, along with other areas, is also involved in making aesthetic judgments. This is quite distinct from other judgments. For example, if you ask subjects to judge which painting is larger, an adjacent but different part of the brain is involved.

You bring up an interesting point, that biological beauty is not as subjective as some may think. But a lot of people associate beauty with symmetry, can that have something to do with it?

To find a face beautiful it has to have a certain symmetry, a certain proportion, and a certain relationship with the partner. But there is another ineffable quality, and no one has been able to express what it is, perhaps with the exception of neural activity. By that I mean that when subjects experience a face as beautiful, a particular pattern of neural activity emerges in the face responsive areas of the brain. It is only when such a pattern emerges, that field A1 is also engaged, thus resulting in activity in field A1. When subjects look at faces that they perceive as being not beautiful or neutral, the face response areas are still active but no pattern emerges in them and there is no activity in field A1.

If you want to define beauty you can give it a neurobiological definition — you can say it’s a situation in which the activity in field A1 of the medial orbitofrontal cortex always correlates with activity in other specific parts of the brain, depending upon the source of beauty.

So, there’s a universal response when it comes to abstract beauty?

No, beauty itself is an abstract experience in the sense that it has many different sources and, for biological beauty, there is a fair consensus among subjects of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds about what is beautiful. This is not so for artifactual beauty, beauty made by human agency. But, whether artifactual or biological, the experience of beauty always seems to correlate with activity in field A1.

So, for someone who has never studied neuroaesthetics, how would you introduce the concept of beauty and the universal or subjective understanding of it.

I would invoke it by saying that unlike what a lot of people think, beauty is an essential and fundamental experience, not something reserved for the rich or the powerful or the leisurely classes; beauty is something we all aspire to and the study of beauty, which is a rewarding experience, should be a fundamental part of any curriculum that is dedicated to studying human behavior. From there, I would jump to Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), who said that one of the most powerful forces in life is the pursuit of the pleasure principle, which, in German, is the Lustprinzip. This has a slightly different meaning than in English because it means both pleasure and desire.

Now the area of the brain which is active when you experience beauty or desire for that matter — the medial orbitofrontal cortex — is part of the pleasure and reward center of the brain. There are many sources of beauty, but there is one brain area, field A1, in which activity always correlates with the experience of beauty regardless of source. But I am anxious to emphasize that field A1 does not act in isolation – it is not what some have called, mistakenly, a “beauty spot” in the brain. Rather it works in collaboration with other areas but what other areas it works in collaboration with depends upon the source of the beauty.

So, neuroaesthetics has brought us a little bit closer, not much closer, to understanding the nature of beauty, but when I say a little bit closer, it is quite a long distance.

You also studied the relationship between aesthetics and love.

“More often than not, romantic love is triggered by a visual input, which is not to say that other factors, such as the voice, intellect, charm or social and financial status do not come into play. It is not surprising therefore that the first studies to investigate the neural correlates of romantic love in the human should have used a visual input. These studies showed that, when we look at the face of someone we are deeply, passionately and hopelessly in love with, a limited number of areas in the brain are especially engaged. This is true regardless of gender. Three of these areas are in the cerebral cortex itself and several others are located in subcortical stations. All constitute parts of what has come to be known as the emotional brain, which is not to say that they act in isolation.”

Beyond that, we go along with Plato’s Symposium (c. 385-370 BCE), which is a big and central reference for us; specifically [a speech in praise of Love (Eros) made by Socrates (470 BCE-399 BCE) describes a journey of ascent from sexual love, through aesthetic appreciation of the body, to a spiritual love of the soul, arriving finally at the contemplation of the Platonic Form of Beauty itself.] I personally do not agree with some of the conclusions in The Symposium, specifically that you can, after a long process, discount the loved person and move on to universal beauty. But, whatever my opinion, Plato’s work has been a huge inspiration.

What do you think may be surprising for people to learn about the field of neuroaesthetics?

The medial orbitofrontal cortex and areas of the brain don't just sit there, waiting for something to happen, they want to be nourished. It’s like the visual brain — did you know that if you were to have people shut their eyes from birth, they would basically become completely blind, even if they open their eyes later on in life? These areas must be nourished all the time. And if you equate pleasure seeking behavior in humans with satisfying the parts of the parts of the brain that are involved in recording pleasure and reward, then you can see that you have to reward these areas. You have to stimulate these areas. For example, designing a good environment for people to live in is really quite important, and tenement buildings have had a very nasty and negative effect, so people escaped these by trying to find somewhere more rewarding to live.

How does someone who is blind perceive biological beauty?

Tactile sense can correlate with beauty. I don’t know if anyone has studied this but, I would predict that if you derive a thrill from caressing a human body, there will be activity in the medial frontal cortex, so I think that what these studies point to is one of the most important strategies that the brain uses about the world at large is abstraction. You can experience beauty from many different sources.

So, it’s a collection of different processes that help us experience beauty but these processes differ depending on the stimulus.

Yes, and involve activity in the pleasure and reward centers, also. That’s pivotal.

Do you have a favorite color?

Green. Bluish Green.

Why?

The sea in places like Italy, Greece and Spain. That sort of thing.

Is that where you like to vacation?

No, I always vacation in France. That’s where my home is.

Who is your favorite artist?

I suppose I would have to opt for Michelangelo (1475-1564). He was a fantastic sculptor, a fantastic painter, and a tempestuous person; and he was a radical person, he thought radically. And he understood that measuring instruments were in the brain, whereas now, people think you always have to measure with a ruler. And he transcended boundaries; he was an architect, he was a poet. So, yes, Michelangelo.

So, would you say he’s been your favorite artist for a long time?

Yes, but the problem with Michelangelo is that I cannot own a Michelangelo.

What kinds of music do you like?

Oh, it’s quite a variety. I like pop music and disco music. I like Richard Wagner (1813-1883). I like Richard Strauss (1864-1949). There’s quite a lot of variety.

In terms of disco music, who did you like?

Bee Gees, Gloria Gaynor, and ABBA — music you can dance to. The problem I have with music is that it’s quite a different experience listening to it on your headset at home and a concert hall. At a concert hall, it’s very very impressive, and I like to sit just behind the orchestra so that I can hear everything. It’s very nice.

What is the best concert you’ve ever been to?

Ahh. I can answer you very precisely. It is a performance of The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) given by The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under Herbert von Karajan (1908-1989). It was perfect. I mean, The Rite of Spring is a fantastic piece, but I wouldn’t say that it’s my top, top, top piece. But this was certainly the top top performance. I’ve never seen any orchestra under any conductor perform with such precision and so exquisitely and doing everything so absolutely right.

I talked to Karajan once, I told him: “It must be fantastic and give you gratification to have conducted so many superlative performances.” And he said to me: “The number of performances at the end of which I said, ‘I got it right,’ I can count on the fingers of one hand.”

What is your favorite museum?

I am very attached to The National Gallery, London. I go there almost every Friday.

Do they have events there?

No, but The National Gallery is free, like every museum should be, because it’s a national treasure. They have a wonderful collection, and every Friday before I go out to dinner, I go to The National Gallery and I look at one or two paintings in detail.

If you pay, you feel like you have to see as many paintings as you can, or spend the whole day. But The National Gallery is free — you can pop in and look at one painting and be inspired for the evening.

When you look at paintings, what do you pay attention to the most? Composition, color, subject matter?

Probably the color, though it depends. But color probably hits me most.

What do you do for fun, aside from visiting the gallery?

What I really like is having nice people around me with whom I can talk. I spend a lot of time doing that. I also do that with people at college, where we have talk sessions and they can say whatever they want. These conversations have been very productive because everyone knows that no one is going to laugh at what they say. I also like taking photographs, but you have to carry around a heavy camera when you go around. And I like painting; I have a studio at my home in France. But in England, it’s too much for me.

You’ve exhibited your work before. Are you interested in showing your art?

No, I do it for myself. The paintings and drawings that I have at home are trivial. I put them up in my kitchen for my own enjoyment. It’s nice to paint in France, because the sun and the colors are much more vivid than they are in London.

You held an exhibition of your artwork at the Pecci Museum of Contemporary Art in Milan in 2011. Do you have a style?

Completely abstract. I had an exhibition — White on White (Bianco su bianco), inspired by Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) — in Italy for sculptures. The art was inspired by what we know about the color systems in the brain. It was based on color shadows, which are produced when white light and light of a given color illuminate an object. I designed the statues with a young colleague and he then made wooden sculptures of them. They were painted in white and exhibited at the Pecci Museum against white walls, but they were illuminated in such a way that the shadows they produced on the white walls were multicolored. It was a fantastic experience.

What are your favorite books?

There is one book that I always carry with me wherever I go — so I have a copy in every suitcase. It is a book of selected poems by T.S. Eliot (1888-1965), namely “Four Quartets,” “The Waste Land” and “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” T.S. Eliot was a very difficult man, I imagine someone very difficult to live with, but he was a fantastic artist.

The other works that I read regularly are those of William Shakespeare (1564-1616) and of Honoré de Balzac (1799 - 1850), a fantastic romanesque writer, who explored the mean side — the nasty side — of people; and though he aspired to the aristocratic status, he described with even detachment the plight of the small people, or people who destroy themselves to satisfy a passion fueled by hatred or greed.

And then I love Constantine Peter Cavafy (1863-1933), who is a Greek poet, he is the poet of the frozen moment, a moment experienced in the past and re-lived in a poem years later.

Do you have an art form that makes you feel love?

Music, certainly.

What was the most interesting project that you’ve been a part of?

I think the work on color vision was very interesting, because you are seeing how single cells respond to the experience of color. It was fascinating. Also, this was 30 years ago, when you were not separated from the data by massive analyses; the cell responded or it did not.

Is there anything you’d like to share that was not addressed?

I will quote Michelangelo: “Love takes me captive; beauty binds my soul.” I think that’s what I seek most, beauty and love.

Would you say that in your life you have experienced a sufficient amount of both?

Yes.

Note* Images are available via Fair Use and the Public Domain.