Humor, Art, and The Creation of the World: The little-known history of French illustrator Jean Effel

- Liz Publika

- Nov 11, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: 2 days ago

by Liz Publika

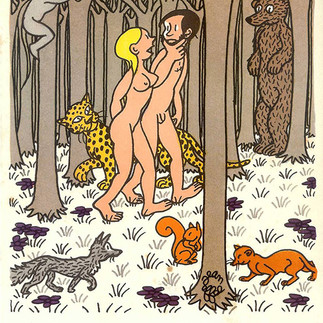

La Création du Monde, or The Creation of the World, is an impressive collection of illustrated books by the French artist, writer, and political commentator, Jean Effel (1908-1982); it is famous for “revolutionizing the book of Genesis through laughter” and, in the history of humorous art, it is regarded as a respected and much beloved staple.

Born François Lejeune, the artist derived his pseudonym from his initials F. L., which he used to publish his works. His parents — a merchant and a language teacher — wanted their son to take over his father’s trade. Effel, however, having studied art, music, and philosophy, chose to follow the path of a creative. After trying to become a playwright, a poet, and a painter, the young man answered a small ad — "Revue seeks designer" — in 1934. Thus began the career of the hard-working autodidact.

Effel’s illustrations quickly found an audience and appeared in numerous French magazines, most of which were closely associated with socialist ideology and sponsored by the French Communist Party. This was not uncommon. Growing up in the 1920s and 1930s, he and his peers were strongly influenced by the horrors of the First World War and its aftermath. It was a time of reflection and major political shifts that took place across the world. Marxism was one of these, and its ideas were prevalent among members of creative communities of the era.

The artist became one of the most sought after illustrators in France by the 1940s. Effel, whose style was clear and linear, predominantly worked in pen and ink. On occasion, he emphasized parts of his illustrations with strategic black markings and poetic accents, such as daisies, birds, spiders, fairies, angels, and his recognizable curly signature. These, some argue, are a reflection of his kind view of the world. "Poetry, fairyland, a sort of mocking and sincere wonder all together are Jean Effel's favorite weapons,” once stated writer Joseph Kessel (1898-1979).

By the end of his life, Jean Effel completed 17,000 drawings and worked on 180 published books translated in 15 languages. Some of his most notable works include a collection of anti-fascist caricatures (1935), illustrations of fables by Jean de La Fontaine (1621-1695), the children's fairy tale Turelune le Cornepipeux (1943), the cartoon book Quand les Animaux Parlaient Encore (When Animals Still Talked) (1953), and the film Les Sept Péchés Capitaul (The Seven Deadly Sins) (1961). Still, his most celebrated work is The Creation of the World.

The entire collection — which earned Effel international popularity for its good-natured folk humor — includes five books: Le Ciel et la Terre (Sky and Earth), Les Plantes et Animaux (Plants and Animals), L'Homme (Man), La Femme (Woman) and Le Roman d'Adam et Eve (Story of Adam and Eve). The lightheartedness of the first illustrations from the eventual collection pleased Emmanuel Berl (1892-1976) — writer and editor-in-chief of Marianne from 1932-1939 — so Jean Effel devoted himself to the theme and expanded it to what we know today.

Most fans of The Creation of the World love the work for its charm. Indeed, Effel's animals and people, God and Red Devil, as well as their respective entourages, are innocent, childlike, and irresistibly endearing. The artist reimagined Genesis steeped in humor, where the characters engage in tireless fun. It’s inoffensive, but witty and sarcastic; and even though the creator of this work was an atheist, his imagined Creator was so kind and loving that even members of the clergy didn’t object to their followers reading the works.

It’s odd, though, that it’s almost impossible to provide a reliable history of the collection’s book releases, as different sources list different dates. What we do know is that the Hermitage Museum’s publishing press released the main collection for the first time in 1963. Interestingly, there are a lot more detailed articles about Effel in Russian than there are in French. This is not completely random as it’s pretty clear that Effel genuinely liked Russians, and knew them well due to his visits to the U.S.S.R. in 1930s and 1940s; he even learned to use Russian letters.

The fact that he did so is not surprising considering that Jean Effel is one of the few people in the world who actually produced a draft of his own universal writing system. His goal was to create something that would link people across their cultural and linguistic differences. So, in 1968, he came up with his own pasigraphy — a written language where each symbol represents a concept instead of a word, sound, or a series of sounds in a spoken language — which he published in a small booklet that can be viewed at the Diderot Library in Lyon, France, today.

“The designer has in fact collected for years, in about fifteen small binders, all the symbols encountered in everyday life, in certain scientific disciplines, in the arts. Methodically classified by major headings, linked to their own meaning and to the meaning they could take on in the universal writing system, all these signs constitute the basis of the writing that Effel imagines.

“There are thus symbols of architecture, electricity, heraldry coats of arms, maritime signage. Mathematical signs also occupy an important place, and the Michelin Guide has been carefully cut to extract all the symbols relating to hotels and restaurants! More finely, Effel also endeavored to work on the necessary nuances of the language, for example with an important work on the ‘transcription’ of adverbs (a lot, badly, almost, etc.), and on the very structure of the language. writing, by studying the root of words and their logical assembly in the sentence.”

If one were to speculate, perhaps the idea of a universal writing system was conceived early on in his career, and tested in Effel’s works throughout his professional life. One example of this hypothesis is the signature daisy that appears throughout The Creation of the World and many of his other works. There’s a good chance that it’s his version of The Daisy Oracle. Originally appearing in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust: Eine Tragödie (1808), the daisy oracle is one of the most prominent instances of flower divination in literary history.

In the book, “Gretchen, who embodies the characteristics of purity and innocence represented by the daisy, is also the agent who destroys the daisy and thus manipulates her own fate, setting the plot in motion,” argues Carrie Collenberg-González. “Some of the most significant iterations of twentieth-century daisy oracles,” she writes, “borrow their form from Goethe.” In other words, the daisy oracle is “an allegory for the self-destructing potential of humankind's striving to manifest its own ideals and nevertheless achieve redemption.”

Since the first book of Faust, much like the first book in The Creation of the World series, is set in multiple locations, the first of which is heaven, it’s not entirely unreasonable to assume that Jean Effel was well aware of the daisy oracle and its associated symbolism. Furthermore, according to Wolfgang Mieder in the Tradition and Innovation in Folk Literature (1987), the daisy oracle “found its way into numerous political caricatures” and the world of advertising — industries that the artist, journalist, and creator of his own language system worked in.

Although the drawings of the smiling God and Devil, Adam and Eve, were likely created in the early 1940s, it wasn’t until after World War II (circa 1957) that The Creation of the World was turned into a film. Thanks to Effel's friendship with writer, artist, translator, and former Czechoslovakian ambassador to Paris, Adolf Hoffmeister (1902-1973), the books were turned into a full-length animated film at Barrandov's Studios. It was directed by Eduard Hofman (1914-1987) and narrated by actor Jan Werich (1905-1980), with Hoffmeister providing the commentary.

Though in his prime, Effel was an international sensation, even receiving the World Peace Prize in 1953, it’s arguable that his work was most popular in Czechoslovakia and the U.S.S.R. For one, he was one of the few artists from Western Europe to have access to countries of the Soviet Bloc. Furthermore, he was a long-time chairman of the Franco-Czechoslovakian Friendship Society and, with Czechoslovakia being the first foreign country to hold an exhibition of his work, it’s fair to assume he was well-liked there.

But, the artist also received the Lenin Prize "for the strengthening of peace between peoples ” in (1967), and became an honorary member of the Academy of Arts of the U.S.S.R. in 1973 as well as the Order of the Friendship of Peoples in 1978. As a matter of fact, his work was such a sensation in the Soviet Union that a ballet of The Creation of the World with a score by Andrey Pavlovich Petrov (1930-2006) was staged in the country in 1971; Mikhail Baryshnikov was among its first, and now most famous performers.

But he was also adored in his native France. Jean Effel died in Paris in 1982. On October 5th the following year, in a rather rare tribute to a humorist, the French Postal Service issued a 4FF stamp to celebrate the illustrator and his sweet version of Marianne, a cheerful young woman with a red cap, who is a national personification of the French Republic, symbolic of liberty, equality, fraternity and reason. It was everything the good natured humorist stood for, and hoped to reflect in the creation of his world.

Note* Images are available via Fair Use.